Should Elder Care be Subsidized? Theory and Evidence from Sweden

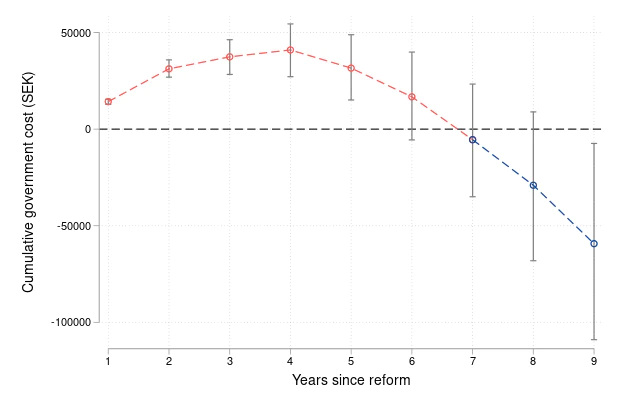

Abstract: This paper examines how subsidies for formal elder (long-term) care services impact the economic and health outcomes of both seniors and their adult children, who often function as informal caregivers to their old-age parents. We exploit a reform in Sweden in 2002 lowering the fee for elder care services by 40% on average across two-thirds of Sweden’s municipalities. Using new data on these fees, combined with administrative data in a difference-in-differences design, we find that increases in the take-up of formal elder care go along with both reductions in hospitalizations among affected seniors and increases in the labor supply of their adult children. Seniors benefit from significant improvements in morbidity, due to fewer hospitalizations for conditions preventable or treatable outside of the hospital. At the same time, adult children increase their annual earnings, which suggests a trade-off between informal caregiving and working depending on the price of formal care. We show that these effects are persistent as adult children keep working in less flexible, but higher-paying jobs, also after the parental care responsibilities have ended. To assess the welfare implications, we build a stylized model that incorporates formal and informal caregiving. We show that the implicit optimal subsidy balances the value created from insuring parents against substantial permanent health shocks and the costs on the children of raising taxes to finance the subsidy. Combining the theory with the empirical results, we find that subsidizing elder care becomes self-financing within a decade of implementation. This demonstrates that the benefits of improved health management and spillovers on adult children can outweigh the direct costs of subsidizing elder care.